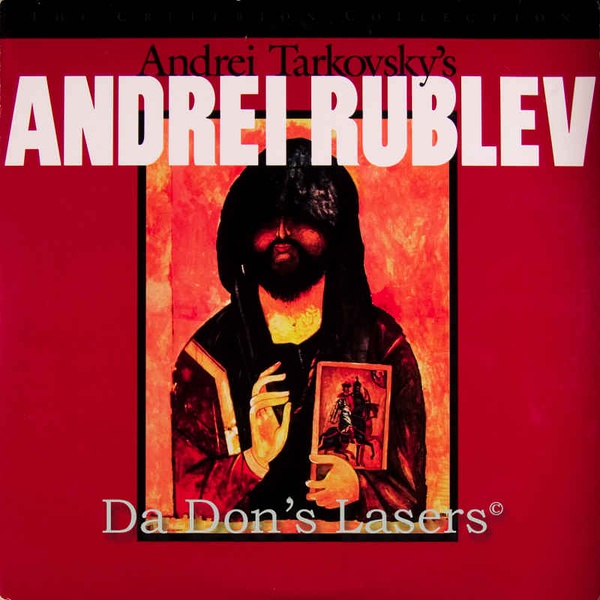

安德烈·卢布廖夫Андрей Рублёв

2013-08-08 06:04 0 3247| 【中文片名】: | 安德烈·卢布廖夫 |

| 【片名】: | Андрей Рублёв |

| 【又名】: | 安德烈·卢布耶夫 |

| 【地区】: | 苏联 |

| 【影片类型】: | 剧情 / 历史 / 战争 / 传记 |

| 【影片年代】: | 1966 |

| 【导演】: | Andrei Tarkovsky |

| 【编剧】: | Andrei Konchalovsky / Andrei Tarkovsky |

| 【主演】: | 安纳托里·索洛尼岑 / Ivan Lapikov / Nikolai Grinko / Nikolai Sergeyev / Irma Raush / Nikolai Burlyayev |

| 【时长】: | Soviet Union: 165 分钟(re-edited version),Soviet Union: 186 分钟(re-edited version),UK: 183 分钟(2004 re-r |

| 【上映时间】: | 1966-12 |

| 【imdb】: | tt0060107 |

| 【评分】: | 8.1 8.9 (1774人评分) |

| 【标签】: | 电影 / 苏联 / 俄罗斯 / 苏俄 / 塔可夫斯基 / AndreiTarkovsky / Andrei_Tarkovsky / 安德烈·塔可夫斯基 |

影片简介

15世纪初,鞑靼人的铁蹄践踏着大公割据的俄罗斯大地,黎民百姓在大公的暴政下水深火热,圣像画家安德烈·鲁勃廖夫就生活在这样的年代。在大公的邀请下,鲁勃廖夫前往莫斯科为教堂作画。但在创作的过程中,鲁勃廖夫却对圣像内容产生了巨大的质疑,这种矛盾的心态使他联想到现今俄罗斯民众经 受的磨难与自己为贵族服务的事实,最终,他毅然离开教堂回到了原先的修道院。

不久,鲁勃廖夫被迫再度回到莫斯科进行圣像创作,但这次他却亲临了所有俄罗斯人的苦难。大公的弟弟勾结鞑靼人篡位谋反,弗拉基米尔城的居民被无辜残杀,教堂在战火中摧毁,画家的眼中全是地狱的景象……鲁勃廖夫再次陷入艺术与现实反差的困境,他又回到安德洛尼科夫修道院,将自己完全封闭,拒绝继续作画。

经过多年的反抗征战,鞑靼人的军队终于被赶出俄罗斯的大地。1423年,大公第三次邀请鲁勃廖夫到莫斯科作画,在一个铸钟少年的感染下,鲁勃廖夫最终完成了《三位一体》的传世名作。

Pros:Gorgeous, painterly cinematography; visually and intellectually stimulating; often rated one of the top-ten films all-time

Cons:Long; lacks traditional narrative design; realistic, gory violence

The Bottom Line: Very different from the usual fare but a brilliant work for viewers attuned to film as art.

Plot Details: This opinion reveals everything about the movie's plot.

If you approach a viewing of Andrei Tarkovsky's Andrei Rublev as you would an ordinary film, you are bound to be frustrated and disappointed. You may have difficulty following the "plot," and you'll probably find it slow paced and terribly long (205 minutes). There's a couple of scenes that are action packed and violent and another with a lot of nudity, so even the most entertainment-addicted viewer will acknowledge "a few good scenes," but will still walk out cursing. Tarkovsky is not for everyone. All Tarkovsky films are beautiful to look at, but only some are thematically interesting – in my opinion. This one is both gorgeous and thematically powerful and cogent.

I might suggest that a Tarkovsky film is a bit like one of those series of frescoes that together depict some Biblical story, but, in this instance, viewers don't already have familiarity with the story, the first time through. It takes a lot of concentration and analysis to piece together the story from the set of largely independent painterly vignettes that Tarkovsky provides. If we applied the same critical standard here that we use in critiquing conventional films, we might conclude that it has a weakness in its script because it lacks narrative clarity. Tarkovsky obviously intends his viewers to have to work hard intellectually while watching one of his films, so it's certainly not in the category of an inadvertent flaw. If you're prepared to watch this film as a series of fresco-like vignettes, understanding that you have to extract some of the elements of the narrative for yourself, you'll discover that Andrei Rublev is, indeed, the cinematic masterpiece that many critics claim it to be.

Historical Background: Andrei Tarkovsky is often described as a cinematic poet and was, in fact, the son of poet Arseni Tarkovsky. Tarkovsky made just seven feature films over a career spanning twenty-seven years. His debut feature film was My Name is Ivan (1962). Andrei Roublev (1966), just his second full-length film, is ranked by many critics among the top-ten most important films of all time. Movie lovers are very fortunate that the film even exists today, much less in the form of the stellar Criterion release of the original director's cut, which hadn't been seen since the film's original screening in Moscow in 1966. Tarkovsky first submitted the proposal for a film on the life of painter Andrei Rublev to a Soviet studio in 1961 and worked on the script with co-writer Andrei Konchalovsky for more than two years. (The script was nicknamed "The Three Andreis" since the title character and both co-authors were all named Andrei.) After the first showing, it was censored and shelved by the Soviets, presumably because of nudity, religious elements, and the depiction of a repressive relationship between a totalitarian government and ordinary Russian people. The film was expressly sought for competition at the Cannes Film Festival in 1969, where it received its first public and competitive screenings and was promptly awarded the FIPRESCI Award, which is what Cannes calls its award for "best cinematography." Even with that recognition, the Soviets stalled the film's general release until 1971, and, even then, with some segments excised. Western distributors sliced out additional footage in at attempt to trim the film down to a length more consistent with the tastes of Western audiences. Happily, criterion has given us the original director's cut, letting us see Tarkovsky's original conception.

The Story: Andrei Rublev is composed of seven chapters plus a prologue and a epilogue. The prologue, entitled "Flying", immediately establishes the mystical or existential character of the film's focus. A man climbs aboard a hot-air balloon perched atop a tower as the peasants below struggle to detach the moorings (while some other peasants try to prevent the launch, fearing what might result from this bizarre excursion into the unknown). The man (and the camera) is suddenly aloft, with the man exulting, "I'm flying." We see what he sees: a dreary tapestry of rivers passing through barren fields, a flock of lambs on the run, and dumbfounded spectators, far below. Finally the balloon and would be aviator come crashing back to earth. We see the "carcass" of the balloon throbbing, as if in death throes. Immediately, the film cuts to a picture of a lone horse rolling on its back, then rising, shaking itself, and gracefully prancing away.

The first chapter is entitled "The Jester, Summer 1400." Three monks are embarking on a journey to Moscow. One asks another whether Moscow doesn't already have enough painters without them. One of the three is named Danil Cherny (Nikolai Grinko). Another is the title character, Andrei Rublev (Anatoli Solonitsyn). Another man, trying to discourage them from leaving, demands to know who will paint the icons if they leave. Rublev was a famous painter of religious icons. The film now cuts to a cabin-like dwelling where the men of a village have gathered for a performance by a jester (Rolan Bykov). This is the most comedic part of the film as the jester gives a spirited and ribald performance about a Boyar who, having shaved his beard, is no longer recognized by his wife. The three monks arrive at the end of the jester's performance, seeking shelter from a downpour. Shortly thereafter, soldiers arrive to apprehend the jester. Jesters, in the fifteenth century were subject to arrest because their free expression was viewed as politically dangerous and sacrilegious. It is suspected that one of the monks had denounced him to the authorities.

A monk named Kirill (Ivan Lapikov), in the second chapter ("Theophanes the Greek, 1405-6"), is envious of Rublev's natural talent. Kirill has traveled to Moscow to meet with an artist, Theophanes the Greek, who has been assigned the job of painting the interior of a cathedral under renovation. Theophanes is in desperate need of qualified help and wants to hire Kirill on the spot. Kirill, however, wants a messenger sent to the monastery to announce that he, Kirill, is requested expressly by Theophanes to help with the painting of the cathedral. Kirill apparently has a need to have his selection witnessed by his fellow monks, especially Rublev, of whom he is envious. A messenger is duly sent by Theophanes, but to request Rublev instead. Theophanes has apparently surmised that Kirill has some unresolved issues relating to vanity. Andrei leaves for Moscow with two fellow monks, who are to serve as aides. While traveling, the monks talk philosophy and religion, as monks are wont to do, and Andrei reveals his vision of The Passion, which is duly enacted as he imagines it.

As they proceed to Moscow, the trio of monks encounter a pagan ceremony on St. John's Eve ("The Holiday") in progress, entailing nudity, debauchery, and fornication. They're having a good old time – in a stream and in the misty woods. Rublev finds himself watching, in spite of himself and his holy vows, especially when one voluptuous woman, Marfa, nestles down with her lover in the woods, just a few feet from where Rublev is standing and hoping to be inconspicuous. So distracted is he, that he even fails to notice, initially, that he has walked into a campfire and his robe has caught fire. Now spotted by the revelers, Rublev is subdued and tied to a cross. Marfa, the sensuous pagan woman, comes to his rescue, demanding to know why he believes love is a sin. She drops her robe and forces a passionate kiss onto his lips before untying him. It's all he can do to flee from temptation. Later, he sees the pagans being persecuted for no better reason than their failure to believe in one god.

In Chapter Four, "The Last Judgment," Rublev struggles with "artist's block." He can't bring himself to paint, after the terrible instances of torture he has seen and the destabilizing affect that the gentle simplicity and hedonism of the pagans has had on his psyche. He's staring to wonder if his pious Christianity isn't just a bit too hypocritical. Grand Prince (Yuri Nazarov), for whom Rublev is painting, has also hired some stonecutters to refinish the cathedral's exterior. When the stonecutters have finished the job, they mention that their next job is for the Grand Prince's brother and that the brother has purchased an even better type of stone for his cathedral. This doesn't sit well with the Grand Prince. As soon as the stonecutters leave, he sends a group of soldiers after them and has their eyes put out in the woods. White paint seeps out of a bottle into the stream.

Chapter Five, "The Raid, Autumn 1408," is the most violent and action-packed scene. The Grand Prince's brother, and rival, has hired a Tartar horde, under the leadership of Tartar Khan (Bolot Bejshenaliyev), to lay waste to his brother's city, Vladimir. This segment is filled with murders, torture, rapes, cruelty to animals, and all the most vicious aspects of human nature, in excruciating detail. We see people being speared and one having boiling water poured down his throat. During the mayhem, Rublev sees a tarter abducting a young mute Russian woman, Durochka (Irma Raush), planning to take her upstairs to rape her. In a fit of rage, Rublev kills the abductor with an ax. By way of penance, Rublev takes responsibility for the mute girl, takes a vow of silence, and determines never to paint again.

In the brief Chapter Six ("The Charity, Winter 1412"), Kirill returns to the monastery, begging for re-admittance. Later, he confesses his feelings of envy to Andrei and admits that he was the one who denounced the jester. A group of Tartars arrive at the monastery and one takes a shine to Durochka and she to him. She rides off with him to become his eighth wife!

The final Chapter, "The Bell, 1423-1424"), finds Andrei Rublev pretty much in the background as an observer, maintaining his vow of silence. The victorious Princely brother wants to atone for killing his brother and the townspeople of Vladimir by commissioning a massive bell, but the master bell-maker has died. His teenage son, Boriska (Nikolai Burlyayev), claims that his father revealed his secrets to him just before his death. He thus becomes supervisor of a team of laborers, all a good deal older than himself, who must cast the giant bell. Their lives are on the line. If the bell fails ring, they'll all be beheaded. Although the boy's father never actually made him privy to his methods, the boy has apparently picked up enough along the way to ensure success. Andrei, who watches the successful testing of the bell, chooses to view the favorable outcome as a miracle or, at least, a confirmation of the triumph of art over the perversity of human nature. Andrei decides he'll give up his vow of silence and returns to the Trinity Monastery with Boriska. There, Rublev will paint his famous "Holy Trinity" and Boriska will cast bells. Afterall, it was Boriska's great bell and the purity of its tone that reawakened Rublev's will to paint.

The epilogue escorts us, for the first time, through a close-up view of some of Rublev's work. Now, suddenly, for the first time, the film shifts to brilliant color, as if to highlight the transcendent nature of Rublev's art.

Themes: The prologue establishes immediately that this film is about mankind's attempt to transcend its corporeal and earthbound existence, to escape physically and spiritually into the cosmos. It is a film about the search for the unknown, with all of the juxtaposition of danger against exultation inherent in such an endeavor. It makes no difference in this respect that the experiment ended badly. It is the search for transcendent understanding that is ennobling, whatever the outcome.

Andrei Rublev is also a film that reaffirms the significance of art as the vehicle by which mankind elevates itself above an otherwise beastly and brutal nature. Art is inherently the search for meanings beyond violence, conquest, envy, greed, and lust. Life in medieval Russia was bleak indeed, with the horrors of famine, the plague, Tartar raids, and the tyranny of the Russia aristocracy. Art and religion shared the task of providing people with some sense of higher purpose as solace for their suffering. Andrei Rublev experiences spiritual angst, due in part to the horrors he observes. He is a wanderer, in this film, in both the physical sense and the spiritual sense – in search of meaning. The film can also be seen as allegorical of Tarkovsky's own search for meaning through art.

Production Values: The script of Andrei Rublev does not follow typical narrative logic. Little is explained overtly and it is often difficult to tie the pieces together as a linear storyline. Instead, the seven vignettes plus the prologue and epilogue are like nine frescoes tied together poetically and thematically. Rublev, as a character, is not a conventional protagonist, either. In some of the segments, he is no more than a peripheral character – a by-stander. Viewers are to identify with him not as a protagonist but as our observer – our eyes and ears. Rublev's state of mind is consequent to the events that he witnesses. We share both his experiences and his psychological responses.

For a film about a painter, it is perhaps surprising that this one withholds any illustration of either his art or his working as an artist until the color epilogue. Instead, we are exposed continuously to Tarkovsky's gorgeous, starkly black-and-white, cinematographic artwork. The photography is really what is most special about any Tarkovsky film. Tarkovsky's so-called "transcendental style" has antecedents in the work of Eisenstein, Bergman, Murnau, and Dreyer.

The emphasis in Tarkovsky's approach to cinematography is on exploring spaces, layering of the field of vision, landscapes, and mise-en-scène. He uses long graceful tracking shot to wend his camera through an architectural space so that the viewer becomes intimate with it. The landscapes are used as dramatic counterpoint to the story elements occurring in the foreground. Oftentimes we see movement in a scene in both the foreground and the background. The camera peers through windows or door arches to transition from one event to another. Oftentimes, Tarkovsky keeps his camera still and uses intricate choreography to move the dramatic events in front of his lens. Fog and smoke, feathers and snow add luster and atmosphere to various scenes. The scene of the pagan ritual is a marvel of mood and mystery. Tarkovsky's mastery of cinematographic artistry is simply unparalleled.

Montage and editing tricks are of minimal importance in a Tarkovsky film, but from time to time he juxtaposes images in a startlingly creative way. A horse rolling in the mud becomes emblematic of the death throes of a balloonist. Aerial images following a shot of the corpse of a swan link the death of the swan back to the crash of the balloonist. Paint spilled into a stream suddenly reappears downstream in a later segment of the film. This is a film that you could justify watching solely for the photography, without even following the story.

Bottom-Line: If you're interested in filmmaking as art – as opposed to merely being entertained – you won't want to miss this film. It is one of the finest examples extant of film as visual art. The Criterion DVD includes new and improved subtitles, an audio commentary for selected scenes from Harvard film professor Vlada Petric, an interview with Tarkovsky, a video essay by Petric on Tarkovsky's oeuvre, and a historical timeline of events in Russian history relevant to the film. Andrei Rublev is in Russian with English subtitles and has a running time of 205 minutes.