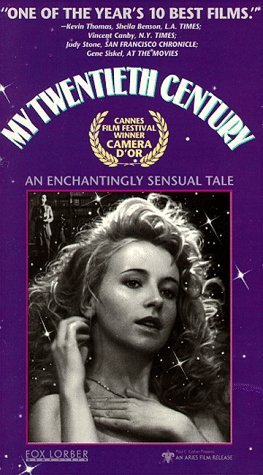

Az én XX. századom

2017-04-12 15:34 0 1291| 【中文片名】: | Az én XX. századom |

| 【片名】: | Az én XX. századom |

| 【又名】: | 我的二十世纪,My 20th Century |

| 【地区】: | 西德 / 匈牙利 / 古巴 |

| 【影片类型】: | 剧情 / 喜剧 |

| 【影片年代】: | 1989 |

| 【导演】: | Ildikó Enyedi |

| 【编剧】: | Ildikó Enyedi |

| 【主演】: | Dorota Segda / Oleg Yankovskiy / Paulus Manker |

| 【时长】: | Hungary: 102 分钟,USA: 104 分钟 |

| 【上映时间】: | 1989-09-15 |

| 【imdb】: | tt0096863 |

| 【评分】: | 7.1 7.7 (187人评分) |

| 【标签】: | 1989 / 1980s / 匈牙利 / 匈牙利电影 / 超现实 / 实验 / 女性导演 |

影片简介

匈牙利著名超现实电影女导演Ildikó Enyedi的代表作品,极度迷幻优美的黑白片,极度富有创意,影片描述一对双生姐妹在20世纪初始时失散又奇特重逢的故事,故事简单,但将时代背景环境运用的恰到好处,可谓一部令人如痴如醉的奇幻杰作。

Dorothy Segda essays three roles in the Hungarian-made My 20th Century. The film begins with the birth of twin girls to a Budapest mother (Dorothy Segda) in 1880. Orphaned early on, the girls are forced to sell matches on the streets until both are adopted by two separate families. Flash forward to 1900: Having lost track of one another, the grown-up twins take separate compartments on the Orient Express. One of the girls (Segda again) has become the pampered mistress of a wealthy man; the other (Segda yet again) is a bomb-wielding anarchist. Director Ildiko Enyedi evidently intended My 20th Century as an allegorical statement concerning the status of women in the modern mechanical age. The experiences of the twins are interspersed with shots of Thomas Edison (Peter Andorai), whom we see at the beginning of the film perfecting his incandescent light bulb on the very day that the sisters are born. The more technological advances made by Edison, the more confused the twins become in establishing their own roles in an advancing civilization. Adroitly avoiding cut-and-dried symbolism, Ildiko Enyedi keeps the audience wondering what she's up to by including such surrealistic vignettes as a caged chimpanzee recounting the day of his capture!

In 1990 Ildikó Enyedi made a Hungarian film about identical twins called “My Twentieth Century.” It played on two theaters in the US (at film festivals) and received its only theatrical release (limited) in the Czech Republic. Vincent Canby gave it a rave review in the New York Times and listed it in his top 10 for the year. Fox Lorber bought the rights and put out a limited VHS run. By 1992 the film was forgotten and it has languished in obscurity ever since

When I was in high school, I watched some Fox Lorber video that included a trailer for “My Twentieth Century.” I no longer recall what movie I was actually seeing, but somehow every image of the intriguing trailer stayed with me over the intervening years. Perhaps my total obsession with movies about twins and doppelgangers (oh, upcoming list idea!) influenced its strange power over me. I recently bought the VHS on eBay and watched it (after receiving two broken copies and eventually having Katie repair one) and found that it fulfilled my every overgrown expectation.

Anya (Dorota Segda) dies soon after giving birth to twins Dora (Dorota Segda) and Lili (Dorota Segda). As shivering Budapest orphans, they sell matches to pedestrians, are visited by a dream-animal and are separated by a pair of silent gamblers who appear only in a single scene. Fate contrives to reunite them at the turn of the century, on board the Orient Express. Though the sisters are now totally different (Dora is a rich, sexually-liberated sensualist while Lili is a reserved feminist anarchist) they fall in love with the same man, Z (Oleg Yankovsky). They remain unaware of each other, and he of their duality, until the films beautiful, ambiguous finale.

Perhaps the most noticeable difference in the film’s approach to cinema is its staggering narrative freedom. Director Enyedi, who also wrote the screenplay, rushes headlong through time and space, yet always has time for humorous, mesmerizing and provocative digressions. A Greek chorus of stars giggle and gossip about the terrestrial events, a lab dog escapes ecstatically elludes his experimentors on new years eve 1900, a trip to the zoo uncovers a monkey who tells of his capture, and Otto Wittgenstein shows up to propound his theory that all women are “either mothers or whores” (he gets soundly booed by his audience of suffragettes).

Most conspicuous are the vignettes that bookend the film, focusing on Thomas Edison. In 1880, Edison is participating in a dazzling light show to demonstrate the marvel of electricity, complete with a marching band wearing helmets plumed by radiant light-bulbs. Yet the inventor looks up at the stars with sadness, perhaps at the failure of his contraption to rival the wonder of the night sky. The stars twinkle and twitter to each other, noticing his melancholy but becoming distracted. “Look over there, in Europe!” “Where?” “In Budapest!” and there, indeed, we see the twins born. Twenty years later, as the film closes, the girls are setting loose messenger pigeons while Edison is unveiling his global radiotelegraph.

Like one of my other favorite films, “A Zed and Two Noughts” (1985), twins are used as a chance to employ unusual structural symmetries. Not only do Edison cameos form a framing pair, so does the appearance of a friendly mule. The system is set up in the birth scene, where their mother holds the sisters side-by-side and their names materialize overhead. Though coincidence keeps them apart for much of the film, Enyedi crosscuts them into mirrored positions and situations, finally reuniting them in a network of actual mirrors.

The film is, as one would expect, surreal and ethereal. It’s also quite confusing at times, but one hardly feels troubled by the uncertainty, symbolism and semi-randomness. It’s clear from the start that Enyedi is having too much fun, covering too much ground and bouncing around too many ideas to catch her breath, let alone to bother much with continuity. Her film captures the spirit of the age, with the impetus of invention, social upheaval and personal freedom. Who cares if it’s accurate: goggle-eyed spectators state hilarious misconceptions, quack sociologists shout silly pseudo-science and Enyedi herself suggests magical explanations where facts are too boring or too slow to serve her purposes. Even Edison seems to wistfully sense that his technological wonders and scientific know-how are a move in the wrong direction; a fanciful delight that illuminates reality at the cost of imagination.

Enyeda casual, encompassing brew of realistic, fantastic and mystic elements creates a modernist fairy tale where twins are divided and reunited, animals speak and cavort and countries like Austria and Romania are just “places that Shakespeare made up.” Enyedi’s tone might be playful, but her message is a clear celebration of feminist potential. Dorota Segda is marvelous in her triple role, and really communicates the wonder and happiness of women exploring the ever-widening possibilities of intellectual, political and sexual life.

Though Dora would seem initially unsympathetic (her inner monologue considers and dismisses men as amusing, occasionally attractive, trifles), her mixture of carefree pleasure and cynical savvy come out as bold, witty and enticing. Meanwhile, Lili has naivity and warmth to spare with political convictions that can get her to light a bomb and a humanist philosophy that prevents her from throwing it. A casual reading might spot shadows of Wittgenstein’s mother/whore dichotomy, but any in-depth experience of the film only shatters his simplistic theory into brilliantly multi-faceted crystals.

Visually, the film looks like almost no other, due in large part to the unusual lighting. It is shot in black and white on starry street corners, rumbling sleeper cars, darkened love nests and even a hall of mirrors within a labyrinth of black velvet and bare bulbs. It has all the darkness of a classic noir, but it isn’t used for harsh shadows and concealed killers. Rather, it serves as a backdrop for flaring lights, refracted steam and sudden close-ups.

There is a visual pattern of soft white lights caught in hazy blacks. Early on there is a camera shot of the moon, made to bounce on the bottom of the frame by carefully bobbing the camera. Edison’s lights, the ever-watchful stars, snowflakes on a Christmas Eve, matchsticks on a bitter night, and fuses on an iron bomb all help to polka-dot the compositions in high-contrast. The emphasis on things that glow without enlightening, people that recede and emerge from shadows and identities that are shrouded in both literal and metaphoric darkness, give the film an enigmatic, secretive feel.

Films like this tap into all sorts of inner spaces and I’m not surprised that it inspired my curiosity across a third of my life. Half the time I wasn’t sure whether I should try and crack the layers of symbolism, search for coded messages, or simply be seduced by the visuals and freeform narrative flow. I’m awfully glad I now own this film, because I’ll be watching it many, many times. --From Film Walrus